Length

3 min read

In digital interface design, two critical elements work together to create an effective user experience: visual design and copy.

The visual design of a digital interface plays a significant role in creating a lasting initial impression. We react emotionally to the visual design before anything else which is why so much emphasis is placed on it. Colour, typography, and layout work together to create an aesthetic experience that guides user expectations.

Equally as important is the copy. It conveys valuable information, often provides directions for users to complete tasks quickly and easily. Effective copy balances clarity, conciseness, and brand voice while addressing user needs and aligning with design strategy.

To enhance the user experience, copy must offer clear benefits while minimising the obstacles to accessing the content. Legibility and readability are crucial for user engagement and ensure users can engage with and understand content.

Improving legibility.

Legibility refers to how easily people can see, distinguish, and recognise the characters and words on a page. Legibility is easy to get right. Font size, contrast, and font choice all contribute to good legibility. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) are a great tool you can use to get started, but do not establish a minimum font size or recommend a specific typeface. For optimal readability, text should follow a few general rules:

- Body text should be at least 12 points (pts), or around 16 pixels (px).

- No text should be smaller than 9pts (12 px).

The WCAG does however, (SC 1.4.4) state that visually rendered text needs to be able to be scaled successfully (up to 200%) so that it can be read directly by people with mild visual disabilities without requiring the use of assistive technology.

Having high contrast between characters and background also improves the legibility. Using a plain background ensures there is no interference with the recognition of the minute details in the letterforms, which is essential to ensure people a language-based learning disability can utilise the interface.

Using fonts that are easy to digest is also recommended. A paper titled ‘Good fonts for dyslexia’, published in 2013, tested 12 fonts to understand if font style affected readability in participants with dyslexia. The paper found Helvetica to be the ideal font to use to accommodate people with Dyslexia. Helvetica had significantly higher reading performance compared to serif, proportional and italic fonts. Participants also stated that Helvetica invoked a sense of trust and clarity.

On Readability.

Readability refers to how difficult a passage in English is to understand.

Good readability improves the likelihood that the reader will clearly understand the contents of a page. Good readability also lessens misunderstandings and lets the reader easily process the information that has been shared without expending a lot of energy.

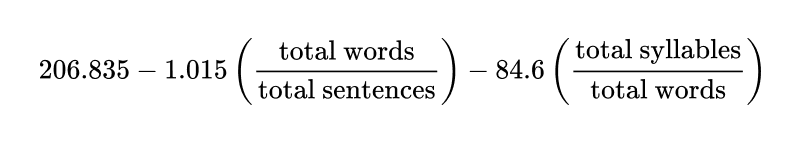

Readability is measured using one of two Flesch–Kincaid readability tests – the Flesch Reading-Ease, and the Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level. Although they use the same core measures (word length and sentence length), they have different weighting factors.

The Flesch reading-ease test uses a mathematical formula to calculate the reading level. Other ways to calculate the reading level include using one of the many free Flesch reading-ease online calculators.

The mathematical formula used to calculate reading level.

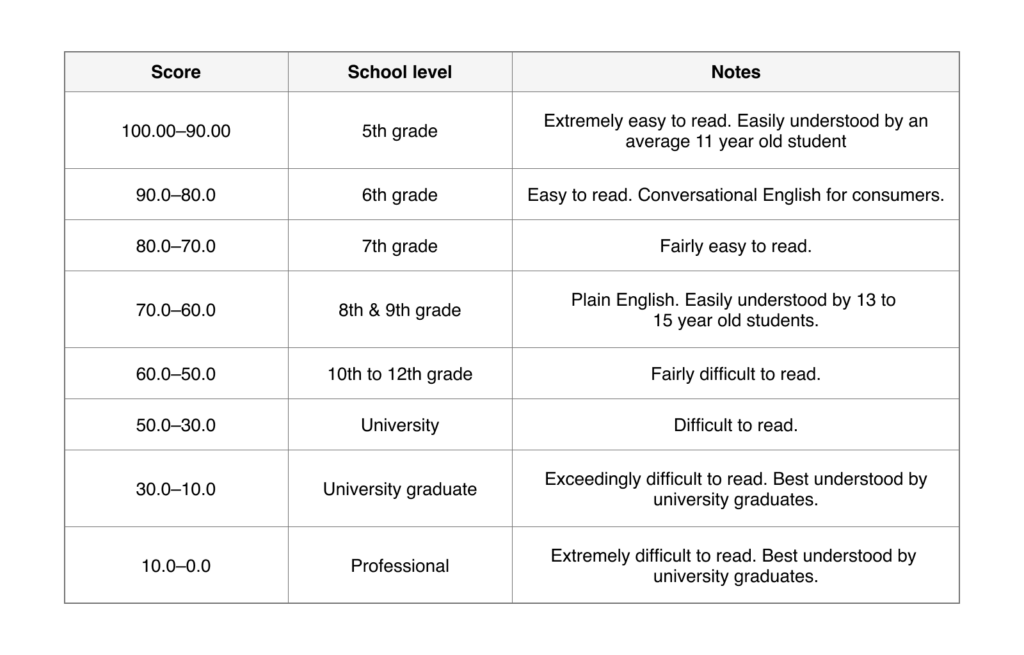

In the Flesch reading-ease test, higher scores indicate material that is easier to read; lower numbers of mark passages that are more difficult to read.

Table showing an interpretation of the Flesch reading-ease scores.

Table showing an interpretation of the Flesch reading-ease scores.

The myth of plain language.

A common misguided objection about a high score on the Flesch reading-ease scale is that plain language dumbs down content and thus insults intelligent readers. This is incorrect. Studies show that even professionals want clear, concise information devoid of unnecessary jargon or complex terms. Plain language benefits everyone.

Optimal Line Length.

Line Length contributes to the readability of copy. Some fundamental exploration of line length and readability was conducted by Emil Ruder, a mid-twentieth century Swiss graphic designer. Ruder concluded that the optimal line length for body text is 50–75 characters per line, including spaces.

If the line length is too long, it can be hard to track where each line starts and ends, which can make reading difficult. If lines are too short, users must move their eyes back and forth too often, which can interrupt their reading flow and cause them to skip words. The ideal line length of between 50 and 75 characters helps readers stay focused and read smoothly without unnecessary eye movement or stress.

A diagram showing examples of line lengths: too short (40 characters), ideal (60), too long (100).

A diagram showing examples of line lengths: too short (40 characters), ideal (60), too long (100).

Things to keep in mind.

Just because users can read the content on a webpage does not mean they will. On average, users read only 28% of the words on a web page because they tend to scan rather than read thoroughly.

To keep users engaged, it is important to grab their attention quickly. Headlines are crucial for this, and the first few words are especially important since people often scan content.

Some things to remember;

- Use clear headlines and a layout that is easy to skim.

- Highlight information that interests users, not just what you want to promote.

- One of the first pieces of content the user reads should outline why content is valuable and relevant.

References.

Rello, L., & Baeza-Yates, R. (2013). Good fonts for dyslexia. Proceedings of the 15th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, 1–8.

International Dyslexia Association. Frequently Asked Questions About Dyslexia.

Readability formulas: Useful or useless. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication. 30: 12–15.

Typography: A Manual of Design, Emil Rudder, 1967

Loranger, H. (2017). Plain Language Is for Everyone, Even Experts. Neilsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/plain-language-experts/

Australian Government Style Manual. (2022). Accessible and inclusive content: Literacy and access. https://www.stylemanual.gov.au/

World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). (2023). Understanding Success Criterion 1.4.4: Resize text. W3C Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI). https://www.w3.org/WAI/WCAG21/Understanding/resize-text.html

Nielson, J. (2015). Legibility, Readability, and Comprehension: Making Users Read Your Words. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/legibility-readability-comprehension/